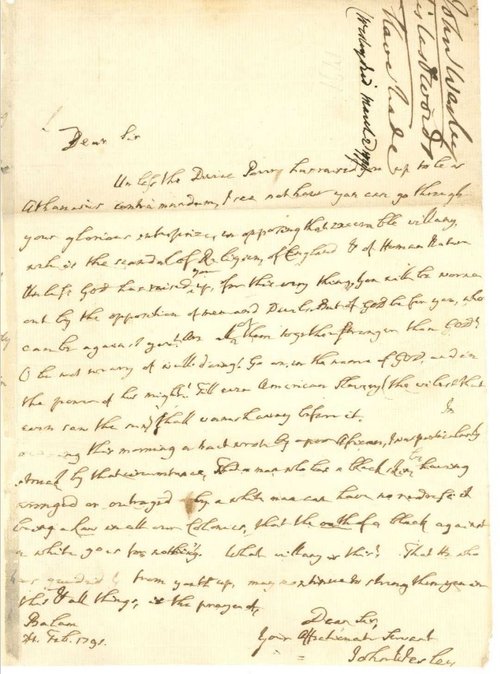

"...I see not how you can go through your glorious enterprise in opposing that execrable villany, which is the scandal of religion, of England, and of human nature. Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you? ..."

John Wesley to William Wilberforce, 24 February 1791

In the eighteenth century England wrung from Spain and France a virtual monopoly of the slave trade and contracted to supply the Spanish West Indies with 144,000 enslaved people within 30 years. But it was also from England that the movement for emancipation sprang. Samuel Wesley senr. was an early opponent of the slave trade: an unsigned article in the Athenian Oracle, for which Samuel shared responsibility with his brother-in-law John Dunton, declared 'I … cannot see how such a trade (tho' much used by Christians) can be any way justified, and fairly reconciled to the Christian law.'

In 1738 Whitefield advocated the introduction of slave labour into Georgia, in order to work the land granted to him for an orphanage, though he envisaged their being humanely treated and taught the gospel. Within two year he had changed his view and published a letter to the slave-owners of North America which aroused fierce controversy. But he still condoned the use of slave labour on the plantation he bought in 1747.

The Wesley brothers had encountered slavery in South Carolina in 1736. But it was not until he was inspired by the Quaker Anthony Benezet, that John Wesley attacked what he called 'this execrable villainy' in his Thoughts upon Slavery (1774) and other writings. In March 1788 he preached on slavery to a large congregation in the New Room and a violent interruption in the middle of his sermon caused 'inexpressible terror and confusion', which he attributed to Satan. In what may have been his last letter, he strongly urged William Wilberforce to continue his battle against the trade.

Visiting the newly independent American States in 1784-85, Thomas Coke found slavery to be too controversial an issue for open denunciation without damaging Methodism's appeal to the American people. He deemed the newly formed church to be 'in too infantile a state to push things to extremity'.

The society and economy of the Caribbean was based on West African slavery, and this presented the missionaries in the West Indies with a dilemma. They were dependent on the goodwill of the plantation owners for their access to the enslaved people whose spiritual good was their primary concern. In the 1780s Coke himself misguidedly bought enslaved people to further the mission to the Caribs of St. Vincent and was severely censured for this. Early missionaries in the West Indies (e.g. John Stephenson in Bermuda, John Barry in Jamaica, John Rutledge in the Bahamas and William H. Rule in St. Vincent) bore witness against the institution of slavery itself and suffered through their opposition to slave-owning. The Missionary Committee in London was firm in its opposition and its rule forbidding missionaries to own enslaved people which created problems for someone like Rutledge, who inherited enslaved people by marriage. In 1807, at Coke's instigation, missionaries were explicitly forbidden to marry any slave-owner, though members of society were not subjected to the same discipline. The response of the Antigua District Synod was that 'the publication of that minute was impolitic, the execution of it impracticable, & the effects of it injurious'.

The situation on the ground was that as the work among West Indian enslaved people developed, the missionaries faced a difficult choice between open opposition to slavery and free access to the enslaved people themselves, which depended on the good will of their owners. The 1822 Instructions to Missionaries insisted that their task was 'to promote the moral and religious improvement of the slaves', without 'interfering with their civil condition'. 'Equality before God' did not imply political or social equality. Plantation owners were among those who welcomed the missionaries and supported the building of chapels, and some of them treated their enslaved people humanely. But others suspected the missionaries of fomenting trouble with enslaved people, especially as the movement for emancipation gathered strength. In 1824 some of the missionaries in Jamaica sought to counter these charges by a series of resolutions in favour of slavery. This compromised the policy of the Committee in London. The Committee censured them and strongly reasserted its anti-slavery stand. James Horne, suspected of being implicated in the 'Jamaica Resolutions', was in danger of being summoned home, but moved to Bermuda, where he continued to serve faithfully until his death in 1856.

The Emancipation Act which came into force on 1 August 1834 owed much to the zeal and conviction of the evangelical leaders of the day. In 1824 Richard Watson had preached a sermon which ably presented the case against slavery, though advocating a gradual and peaceful process towards its abolition. The Wesleyan Methodist Conference in 1830, at Watson's instigation, adopted a series of resolutions against slavery anywhere in the British Empire and exhorted local congregations to sign petitions against it. The Wesleyan Methodist layman Richard Matthews was prominent in the anti-slavery movement, serving as secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society and on the sub-committee of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society dealing with schools in the West Indies.

Later in the century American slavery was an issue which split the Methodist Episcopal Church as well as the nation as a whole.

Authored by Kenneth G. Greet and Norman W. Taggart for DMBI: A Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland. NB: Some of the wording in this text has been minorly altered to replace outdated terminology.